“Kiwis evoluted,” the eight-year-old with fiercely black and independent hair shouted when I called upon him to respond to my question about the bird’s inability to fly.

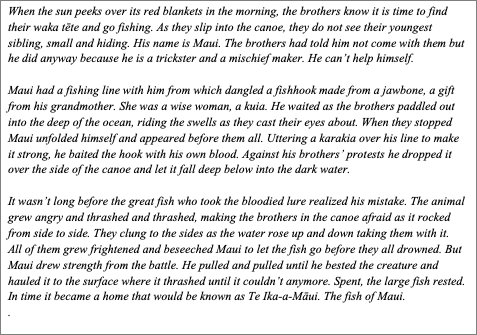

The boy answering my query was in an American second grade classroom where I had twenty-five pairs of eyes fixed on me. I’d just told the kids the Māori tale of Maui’s great battle with the fish that became the North Island of New Zealand.* My telling of it was greeted by the class members with the usual full range of responses—stout disbelief to a glorious willingness to suspend the same. On this day I pointed out the North Island on the class map and the kids peered at it, trying to see if it was sufficiently fish-like in appearance to support the claims of the tale. From there I held up a picture of a kiwi bird, noting it is New Zealand’s national icon and that Kiwi is what New Zealander’s call themselves. I asked why the birds could be seen only among the plants of the country at night rather than flying.

“It doesn’t have wings anymore,” said the boy who had waved his hand determinedly, more animated by the science than the story. “The kiwi birds stopped using wings because they didn’t need them. They…” He groped for the word and finally blurted out “evoluted.”

‘Evoluted’ became a word in our house after that story telling session. The condition to which the child was referring is interesting to observe in oneself. My personal evolution began, as do most, in the teenage years. It was then I became aware that my homeland was a long way from anywhere on the globe. Perhaps it was the comment from a Dutch immigrant that New Zealand was a “pimple on the bum of the world” that did it. In any event, my sights were rigidly outward during my 1960s high school years when I wanted nothing more than to leave the country and see what I was missing.

The June visit of Tyson, my Seattle-based girlfriend became an opportunity to reflect on how far I have ‘evoluted’ back into being a Kiwi after ten months living full-time in the country. I looked at the iconic experiences on offer through fresh eyes after 47-years away exploring the world. Most notable for me was the trip to Rotorua, my hometown.

It was full of mud pools when I lived there. They are still around of course, cauldron-like, extraordinarily hot, and plopping in soft arrhythmic explosions that push a column of mud into the air. When the column collapses it flicks off volcanic ash and clay along with belches of hydrogen sulfide. Before rain the air often smells like rotten eggs. As a child I loved the rising steam everywhere, the sulfuric pungency, the feeling as I rode my bike to school that the volcanic world below my feet was alive.

On my visit with Tyson I rediscovered my unique resonance with the place. It is hard to describe. Poet T. S. Elliot, who was raised in St. Louis, experienced this same feeling about growing up by the Mississippi River.

I feel that there is something in having passed one’s childhood besides the big river which is incommunicable to those people who have not.

This is my home and so the feelings are deep enough to be incommunicable. It was where I started from, a part of the land to which I am ‘evoluting’ back and treasuring in a way I never did before. In Rotorua, a little conversation at a cultural event that showcased the Māori traditional way of life and thinking taught me something else that is helping this ‘evoluting’ process. At dinner, Tyson and I were assigned a place next to two American women. I asked them if they had seen the ‘haka’ or traditional dance that was part of the concert enjoyed before we sat to eat. The younger of the two lit up. “I have,” she said. “At my sister’s wedding.”

It appears New Zealand is no longer a little pimple on the bum of the world!

*Te Ika-a-Maui/The Fish of Maui